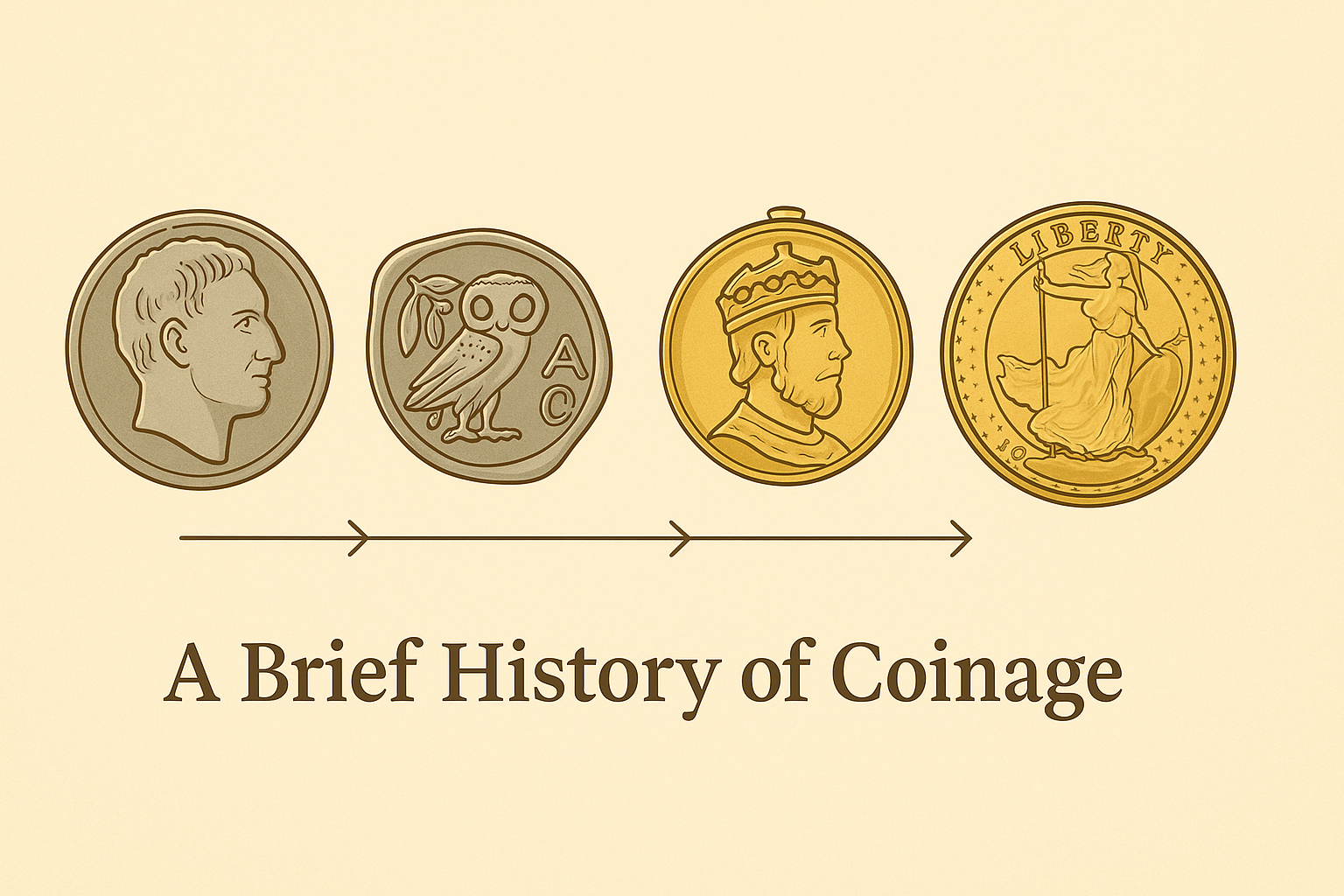

The history of coinage goes back a very long time. People have been making coins by melting and shaping metals for thousands of years. They needed a way to buy and sell things that was easy to carry and use.

A history expert, Dr. Thomas Figueira, said coins changed how people thought about value. It was a big change for everyone.

Many people like collecting coins and dream about finding new ones. But do we know the stories behind them?

Keep reading to learn about the interesting history of coins and why they mean much more than just money.

Time Before Coinage: Items From Nature

The earliest forms of money included natural objects. Cowrie shells, originally used as currency around 1200 BCE, are a famous example. The shells offered several benefits despite appearing to be a rather random choice – they were comparable in size, compact, and robust.

Even though the mollusks that make the shells are found in the Pacific Indian Ocean’s coastal waters, trade expansion allowed certain European nations to use cowrie shells as money. Native Americans utilized wampum, which is tubular shell beads, as currency.

Whale teeth were another form of natural currency used by the Fijians. Additionally, the inhabitants of Yap Island (a part of modern-day Micronesia) carved large limestone disks that later served as coinage and are now an important aspect of the island’s culture.

Money had been an idea for a while. Ancient Mesopotamians even had a banking system in which people could “deposit” cattle, grains, and other goods for safekeeping or exchange. In ancient China, seashells were used as currency nearly 5,000 years ago.

The First Coinage: A Lydian Production

Around 600 B.C., the world’s first coinage appeared clanking in the pouches of the Lydians. Located in modern-day Turkey, Lydia was a kingdom with connections to ancient Greece.

These first coins were composed of electrum, a natural alloy of gold and silver, and had a lion’s head sculpted on them. They had a rough shape that resembled a bean, but they also had a regal emblem that gave them the air of authority people would recognize today.

The coins may have been weighed to assess their value, according to speculation. This makes sense given how challenging it was to come up with a uniform look for every coin. Since the coins were being used in their original form, they also came in a variety of sizes and shapes.

They first arose between 610 and 560 BCE, during King Alyattes’ reign. The kingdom’s coinage was changed by Alyattes’ son Croesus (reigned 560–546 BCE), who introduced silver coins and gold coins. Such currencies soon started to emerge elsewhere.

The Subsequent Followers: Greek City States

Soon after, when the Lydian experiment seemed to be succeeding, shiny new coins started to appear all around the Mediterranean. By the sixth century B.C., Athens, Corinth, Aegina, and Persia had all produced their own coinage, which made it easier than ever to expand trade networks.

The preferred material was changed from electrum to gold and silver, and coin denominations reflected the actual worth of the metal rather than a fixed amount, as is the norm with modern money. The same practices were later used for Roman and Celtic coinage.

Coins From Ancient China: Another Early Mintage

Ancient China also produced the earliest known/what is coins during the same timeframe as the Lydians. Before the invention of these coins, the Shang Dynasty employed cowries, the shells of sea snails. Later, inscriptions representing Chinese cities were engraved on pieces of gold. Following this, knives made of different metals served as currency.

The exact date of the invention of coinage in China is unknown. This is because Emperor Qin Shi Huang, the first ruler of the unified empire of china (formed in 221 BCE), destroyed as many documents of previous Chinese dynasties as could to sustain the stability and inclusiveness of his newly-formed empire.

Chinese currency adopted a single form after the Qin dynasty established a unified empire in 221 B.C. — the traditional round pan Liang, or ban Liang, 1/2 ounce coins featuring a square hollow in the middle. The weight of the coin was indicated by a two-character legend on these bronze coins.

Coin money didn’t become widely used across the region until around 220 BC. The majority of these ancient Chinese coins include a hole of some kind, either square or circular. This was purposefully designed so that coins may be transported more easily by being attached to a thread or wire.

Roman Modification Of Coinage: The Inception Of Fiat Money

Around 27 BCE, the Romans created a system whereby the value of coinage was determined by what was written on it rather than by how much it weighed. This was the first step in the direction of fiat money. This is what permitted the Romans to eventually devalue their money by reducing the volume of precious metals within every coin.

This mechanism reduces the value of each coin since the coin would always claim it is worth $5, for example. However, if the coin’s gold content drops from 90% to 25%, each coin will be worth less than $5.

For their coinage, the Romans used bronze, copper, silver, and gold. They had these denominations early on –

From 27 B.C. to 212 A.D. – 400 copper coins equal 100 bronze coins/ 25 silver coins/ one gold coin, or first 1/40 lb., then 1/50 lb. of gold.

From 294 to 312 A.D. – 1000 pieces of degraded metal equal 40 bronze coins/ 10 silver coins/ one gold coin, or 1/60 lb. of gold.

From 312 A.D. onward – 180 bronze coins equal 24 silver coins/ 1 gold coin or 1/72 lb. of gold.

Emergence Of Coins In The British Isles

Coins are believed to have arrived on the British isles several hundred years later, sometime in the second century BCE, brought by merchants from northern France. Around the first century BCE, the first-ever coins produced in this region were Potins, which had a rough bull design on one side and an Apollo bust on the other. They were made of an alloy of zinc, copper, and lead.

Tribes throughout Britain started minting their own silver and gold coins within a few years. They were referred to as Staters, and each tribe was represented by intricate artistic designs in various shapes and styles.

Roman invaders brought their own coinage with them during the first century CE, and these coins swiftly took the place of Celtic coins from the Iron Age. Up until the Romans left Britain in the fifth century taking their coinage with them, this situation remained unchanged.

Britons returned to the ancient practice of bartering rather than replacing iron-age coins with new ones, and coins didn’t become widely used again until the Anglo-Saxon era.

From the 7th century through the mid-17th century, commemorative coins were created at several mints around the British Isles using various precious metals like silver, gold, and also, bronze in a variety of sizes and shapes to suit varying levels of trade. These ‘hammered’ coins initially had pretty basic shapes and forms, but with time, they evolved into ones with more intricate and lovely designs.

Coin Minting Before And During The Industrial Era

There had been several editions of circulating coinage throughout the birth and boom of the industrial era and prior. Let’s take a look at them –

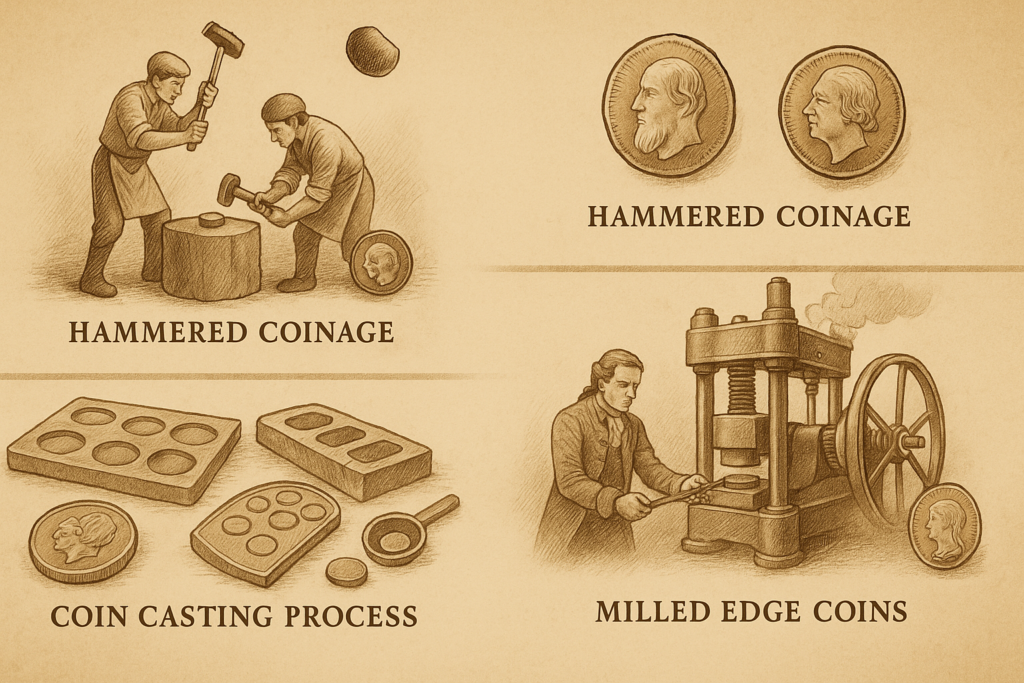

The Hammered Coinage

Until 1550 AD, the method of producing coins involved putting metal pieces between two dies and striking them. This labor-intensive procedure, sometimes known as ‘hammered coinage,’ usually required two people – one for hammering and one for holding the minting dies in place.

Eventually, numerous coins could be produced simultaneously using sheets of metal with the appropriate diameter. This was done to satisfy the growing need for coins for use in commercial transactions.

Unfortunately, a few issues were brought up by this process. The coins became more generic when numerous coins were created at once. It made counterfeiting coins easy. That’s because no coins had the precise diameter that was desired. The coins weren’t exactly round, either. As a result, precious metals might be stripped from the coins’ edges.

These are the reasons a different approach was necessary. However, the technology to develop a superior procedure wasn’t accessible right away. But the Renaissance as well as the subsequent Industrial Revolution later made that possible.

The Coin Casting Process

Melted metal is poured into a readied mold during the casting of coins. In ancient times, this procedure served as a substitute for coin production. Asia was where it was most commonly used.

A dozen coins can be produced from a single mold instead of only one after each strike, making this approach more efficient than the hammering method. Furthermore, more refined, cleaner coins were made, preventing the production of fake coins and the removal of precious metal pieces from coins.

Milled Edge Coins

‘Milled coinage’ gained popularity throughout the Industrial Revolution. This procedure, also referred to as ‘machine-struck coinage,’ essentially entails producing coins by a machine.

The Watt steam engine was invented during the course of the industrial revolution. Every sector of manufacturing businesses deployed this steam engine. The demand for more coins increased significantly as more people began working in industries.

At that time, a financier by the name of Matthew Boulton utilized this steam engine to operate a coin-producing device. This experiment ultimately resulted in two contracts – one to supply equipment to the British Royal Mint, and another to mint coinage for the East India Company.

Conclusion

Everywhere they came, coins offered social freedom of movement to those lacking it. Additionally, most cities had unique designs that were meant to express local pride.

Early on, there were some issues to deal with, largely due to the sheer number of different kinds of coins in Europe. But things got sorted as the progression kept on going, later arriving in this modern age.

FAQs

When Was The First Coinage?

In the sixth or fifth century BCE, coins were first used as a form of payment. Herodotus asserts that the Lydians were the first to produce coins. However, according to numismatists, the first coins were struck on the Greek island of Aegina by either the local king or Pheidon of Argos.

Via the Greek trading station of Naucratis within the Nile Delta, Samos, Miletus, and Aegina, all produced coinage for the Egyptians. The introduction of coins to Persia is unquestionably a result of Lydia’s conquest by the Persians in 546 BCE.

What Was The Process Of Coinage Called?

The process of producing coins is known as minting, coinage, coining, etc many terms. Depending on what kind of coin is to be produced—circulation, collectors’, or investment—the coining process varies.

A coin die refers to each of the two metallic pieces used to strike the coin, one for each of the coin’s sides. Before the modern era, these dies were handcrafted by artisans called engravers.

In troubled periods, like the Roman Empire’s crises in the third century, coin dies were still utilized despite being exceedingly worn or cracked.

Ancient coin producers, a case in point, the Amphictyonic league of Delphi, may have gotten approximately 47,000 strikes from a single die, according to archaeological evidence combined with historical accounts.

What Was The First Coin Called?

Lydia, an Anatolian monarchy with links to ancient Greece, is credited with creating conventional coinage. It makes perfect sense that the coins made in the land of the majestic King Croesus would be of dazzling gold and silver.

The first coins ever made were the ‘Gold Staters’ from Lydia. This Lydian Stater would become the official coinage of the Lydian realm that lasted many years before being conquered by the Persian Empire.

The oldest known coins are thought to have been produced in the later part of the seventh century BCE, under the rule of King Alyattes, Croesus’ father, who ruled from 619 – 560 BCE. However, at first, they were nothing more than metal lumps with simple stamps. With the enhancement brought about by King Croesus, they soon developed into stunning works of art by themselves, portraying figures from Greek mythology.

Numismatic historians believe that these coins, Lydian Starters, were the very first coins to be minted by a government, therefore, set the precedent for nearly all later coinage worldwide.

Who Was The First Person On A Coin?

In the initial days of coinage, symbols were depicted, and also, gods and goddesses or other features that unified the coining culture. To coin portraits, though, was still far away. Humanized deities were shown, not with particular characteristics, but with features associated with rulers.

Tissaphernes (445–395 BCE), a Persian aristocrat and satrap of Lydia, was the first real human to venture to have his features depicted on coins. His practice was quickly copied by other Persian kings, although it would take a little longer for the western world before the portrait was engraved on coins.

What Is The Second Oldest Coin?

Coinage first became widely used in everyday commerce once the Ionian Greeks introduced and popularized the ‘noble’s tax token.’ Around 600–500 BC, Cyme, an affluent Ionian city bordering Lydia, started to mint coins. These hemiobol coins, which feature a horse head stamp, are generally recognized as the second-oldest coins in history.

Half an obol, or hemiobol as it is known now, was the unit of currency used in ancient Greece. Plutarch claims that the name comes from the fact that obols were originally bits of copper and bronze before coinage was invented. Six obols, which are translated as ‘a handful,’ are equivalent to one drachma in the ancient Greek monetary system.

What Is The Rarest Coin In History?

A 1794 Flowing Hair Silver Dollar that was one of just 1,758 coins minted sold for $6,600,000 in August 2021 at auction. Only a few of the Flowing Hair Silver Dollars are thought to remain in existence today, therefore a coin in such condition is incredibly rare and highly valuable.

Due to its scarcity and inherent value, this coin is among the most frequently reproduced or counterfeited coins that dealers receive calls about both domestically and internationally.

Another well-known rare coin is the 1804 Silver Dollar – Class I. This coin is renowned as the ‘King of US Coins’ with good reason – just fifteen specimens of this coin are known to be existing in the world. The coin was minted in 1834, three decades after its original date, and sent as a gift to Asian rulers when trade envoys visited. One of these silver coins was sold for $4,140,000 in 1999.

What Is The Most Famous Roman Coin?

The Ides of March Denarius is arguably the most famous Roman coin. It contains a storied history of Julius Caesar’s assassination by Brutus.

There are currently only 80 known specimens in existence worldwide. Therefore, it isn’t unusual to encounter a price tag for this coin in multiple six figures. One Eid Mar denarius coin was sold on October 30, 2020, for a whooping, record-breaking 2.7 million pounds (around 2,988,360 euros) at Roma numismatic auction.

The coin’s motif refers to Julius Caesar’s assassination on the Eid Mar. (Ides of March). The reverse features two daggers and a felt hat worn by liberated slaves, known as the pileus, while the obverse portrays Brutus. These design elements interpret both the assassination as well as the fact that the assassins believed Caesar to be a tyrant, and killing him was therefore a heroic act carried out to protect the Republic.

![Read more about the article What Is A Clad Coin? [Everything You Need To Know]](https://coincollectorium.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/ChatGPT-Image-Jun-20-2025-12_04_33-AM-300x200.png)